Lecture kindles interest in folk culture

Writer: Debra Li | Editor: Doria Nan | From: Shenzhen Daily | Updated: 2018-04-02

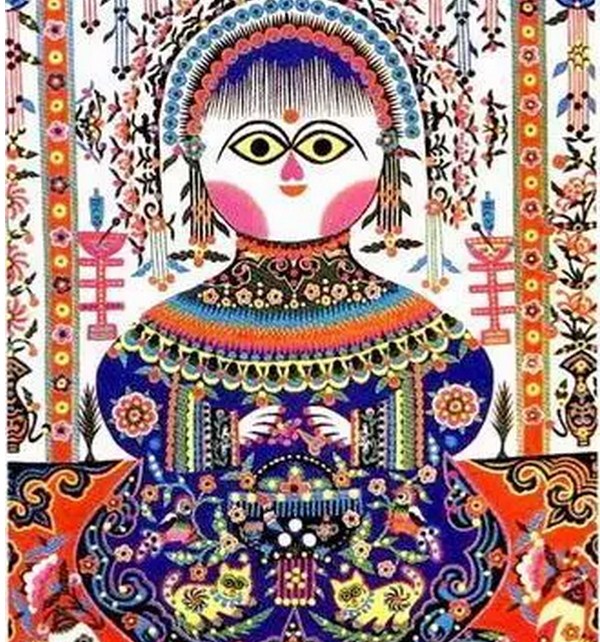

Living from hand to mouth in a poor village in Northwest China’s Shaanxi Province in the 1980s, Ku Shulan found solace in papercutting, a traditional handicraft she learned from her mother. With no extra money to buy ready-to-use pieces of color paper, she collected the scraps left by others at village fairs, categorized them by color and texture and cut them into tiny dots, before making them into a piece of colorful collage work. One marvellous piece depicts a woman with a shallow basket and scissors on her lap, which she named “Papercutting Lady,” a reflection of her self-image.

“Papercutting Lady”

“The work is made of more than 2,000 colorful dots she cut from scraps,” said 74-year-old Huang Yongsong, founder of Echo of Things Chinese, a Taiwanese magazine that has exquisitely recorded Chinese folk culture.

“It’s an unbelievable feat to accomplish, considering the fact the old lady had never received any formal artistic training, inflicted by illness and poverty and not supported by her family,” Huang said during a lecture Sunday morning at Artron Art Center in Nanshan District. Getting married at 17, Ku gave birth to 13 children but lost 10 of them to disease and famine. Never giving up papercutting until her death, Ku left a cultural legacy rediscovered by Huang and brought to a large audience. The papercutting works of Ku were featured in Huang’s magazine and later exhibited in and collected by museums in France, the United States, Germany and some Southeast Asian countries. In 1996, Ku was named by UNESCO an outstanding Chinese folk art master.

Huang, a folklorist born in Taoyuan County, Taiwan and educated at the Taiwan College of Arts (the predecessor of Taiwan University of Arts), started his lifelong cause of setting up a gene pool for Chinese folk culture in 1971, when he was invited to start the English edition of the Hansheng (汉声) magazine.

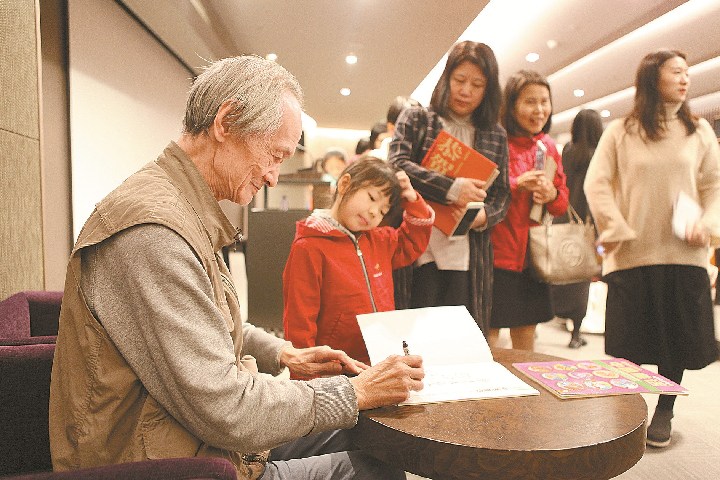

Huang Yongsong signs on a book for a child after a lecture at Artron Art Center on Sunday. Courtesy of Artron

“Taiwan in the 1970s experienced a strong impact from Western culture, and many young people worshipped everything from the West,” Huang recalled. “China has a long history and a huge population, and it’s just not right for the Chinese cultural traditions to be missing from the world stage.” Echo of Things Chinese, the English edition, took up the mission to introduce Chinese folk culture to foreigners. Huang was also involved in the editing and publishing of the Chinese language magazine as well as books on folk culture and folklore for children.

Chinese knots, one of China’s most ancient folk arts, are beautiful plaited ornaments made with colorful silk threads, primarily red. Nowadays, the knots are widely used as ornaments for clothing as well as for decorations in homes. A symbol of traditional Chinese culture, Chinese knots’ popularity can be largely attributed to Huang’s efforts. In 1980, Huang learned knotting methods from old craftsmen and came up with systematical theories on how to make Chinese knots. Three books were published on “Chinese Knotting,” a name Huang and his team coined to sum up the various knotting skills, later translated into English and German.

“German people’s love for handcrafts left a strong impression on me,” Huang recalled. “When I suggested that we add information as to where to buy the threads needed to make the knots, our German publishing partner told me that was unnecessary since they can easily buy the stuff at craft workshops across the country.”

Resist dyeing, a traditional method of dyeing textiles with patterns, is another topic Huang thoroughly studied. Methods are used to “resist” or prevent the dye from reaching all the cloth, thereby creating a pattern. The most common forms use wax (batik) or a physical method that manipulates the cloth such as tying (tie-dye) or clamping it between engraved woodblocks (similar to prints).

In the fall of 2002, Huang and his editors traveled extensively in western and northern Guizhou Province to search for batik works for an exhibition. When Huang offered to buy a piece of a perfectly-batiked baby bundler local women use to carry kids on their backs, the creator, a 102-year-old woman, implored to cut a small piece from it. “I want to keep its soul with me,” she said.

Sharing stories of the past generations, Huang was overjoyed to find many children in his audience at the lecture.

“I’ve heaped up the hope of carrying on our rich folk cultural heritages onto the young, and I’m not disappointed today,” he said.

Many of Hansheng’s publications are available at Artron Art Center.

Add: 19 Shenyun Road, Nanshan District (南山区深云路19号雅昌艺术中心)