Woven in time: The past, present, and future of Xiabu

Writer: Sterling Platt | Editor: Lin Qiuying | From: Original | Updated: 2025-10-22

Stepping out of the southern heat and into the cool, stone-walled galleries of Nantou Ancient City feels like crossing a threshold in time. Here, amidst the preserved architecture of old Shenzhen, the “Summer’s Breeze: The Living Art of Ramie Cloth” exhibition introduces visitors to Xiabu (夏布), a textile described as a “breathing fabric,” and poses a quiet but profound question — what does it mean for a fabric to breathe?

The embodied knowledge of Xiabu has been passed down through generations of skilled hands. Photos by Sterling Platt

Xiabu is one of China’s most ancient textiles, a foundational material woven into the nation’s history for over 4,700 years. For millennia, it was the essential cloth of summer life, yet today it has faded into near obscurity, a whisper from a pre-cotton world.

Rather than a quiet memorial to a lost art, this exhibition tells a dynamic and hopeful story, weaving a three-act narrative that honors a precious heritage, confronts its precarious present, and inspires a vibrant future. It is a masterfully curated journey that transforms a museum visit into a compelling argument for the revival and reimagination of an extraordinary textile.

Honoring the past — The dance of hands, earth, and time

The exhibition’s first act is a powerful immersion into the world from which Xiabu was born. Here, in a region like Guangdong long known for ramie cultivation, the story begins not with a finished garment, but with the soil itself.

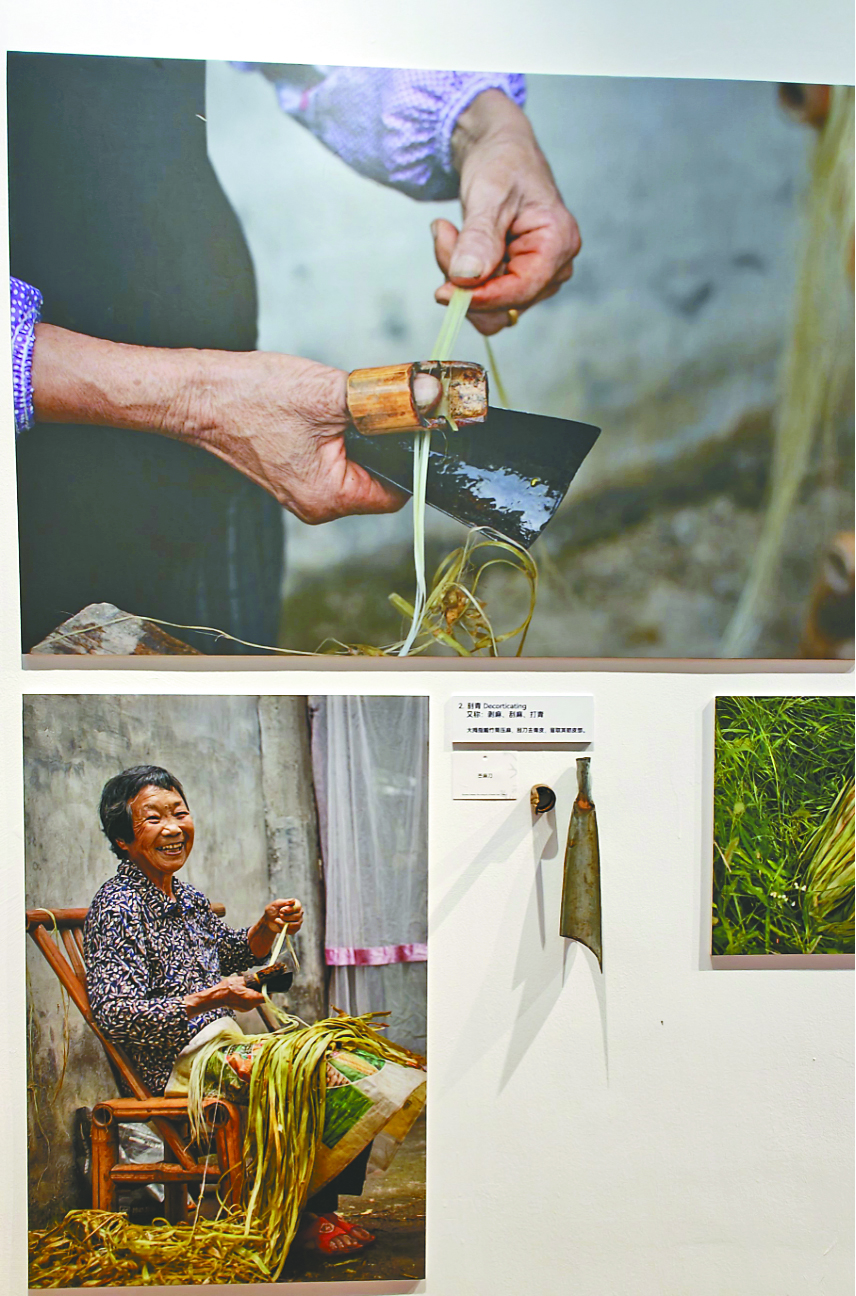

The curators call the process “a co-dance of season, earth, and hands,” and a stunning photo series brings this poetry to life. We see the raw ramie plant, often called “Chinese grass,” being harvested, and the gnarled, knowing hands of an artisan scraping the green bark from the stalk to reveal the silvery fibers within. The process is intimate, elemental, and overwhelmingly manual.

From stalk to thread: A visual timeline of the painstaking metamorphosis of ramie.

This is the central truth of Xiabu — its value is measured in human time. A display shows the material’s transformation from coarse stalk to fine, continuous thread. This second step, connecting individual fibers by hand into a single yarn, is a monument to patience.

As the exhibition notes explain, a skilled worker might spend an entire day producing just 50 grams of thread. Creating enough thread for a single bolt of cloth requires a full month of this dedicated, painstaking labor. This slow, meditative act of creation is a form of embodied knowledge passed down through generations.

The intricate engineering of a traditional “waist loom” loom, a testament to ancient science and artistry.

From this meticulously prepared thread, the cloth emerges. Dominating the room is a magnificent wooden loom, a model of the backstrap loom documented in the Ming Dynasty-era encyclopedia “The Exploitation of the Works of Nature” (天工开物). The 17th-century author Song Yingxing called it a “waist loom” (腰機) because the weaver’s force “is entirely on the waist and hips.”

He praised its capability of producing ramie cloth that was “more orderly, firm, and lustrous” and lamented that its use was not more widespread. On such looms, artisans transformed humble grass into fabrics poetically described as being “as light as a cicada’s wing” and “as smooth as a water mirror.”

These fabrics were the very texture of pre-modern Chinese life. In a climate where summer heat and humidity were relentless, Xiabu was the high-performance, sustainable solution. It was the primary textile for daily clothing long before the widespread arrival of cotton. Displays of historical indigo-dyed garments confirm this. Their simple, elegant forms speak to function and comfort, but their very existence speaks to a deeper history.

The discovery of a fine ramie robe in the 2,000-year-old Mawangdui Tombs, an elite Han Dynasty burial site, confirmed Xiabu’s status as a material cherished by all — from farmers to nobility. To stand before these garments is to feel the tactile memory of a civilization, a direct, physical link to the daily lives of people in a world before industrial fabrics.

Confronting the present — A fading echo

Walking from the reverent displays of the past into the next gallery, the tone shifts. The vibrant world just described has, for the most part, vanished. This section of the exhibition confronts the central conflict in Xiabu’s story: its near-total eclipse in the modern era.

The 20th century, with its relentless logic of industrialization, unraveled this delicate tapestry. Cheaper, mass-produced textiles, particularly cotton, flooded the market, and Xiabu’s greatest cultural assets — the immense time, the irreplaceable skill, the very touch of the human hand — became its greatest economic liabilities.

As the exhibition preface soberly notes, Xiabu has “faded from the fashion world” to become a “marginalized craft,” receiving “limited scholarly or curatorial attention.” The consequences have been devastating. As new opportunities emerged in factories and cities, the intricate knowledge of Xiabu became a fading echo in the memory of elders.

Echoes of the past: Historic Xiabu garments that clothed generations.

The generational chain of transmission, the lifeblood of any intangible cultural heritage, began to break. Master artisans struggled to find apprentices willing to undertake the arduous, low-paying work of their ancestors.

This perilous decline is what makes the exhibition’s focal point here so significant. In 2009, the traditional weaving techniques of Xiabu were officially designated as a national intangible cultural heritage. It was a formal, State-level recognition of the craft’s profound cultural value, a crucial step in rescuing it.

However, it was also a stark admission of its profound fragility. This section doesn’t offer easy answers. Instead, it frames the urgency that underpins the entire exhibition. It makes the visitor a witness to the stakes, asking a critical question: how do you save a craft whose essence is the one thing modernity cannot afford — time?

Inspiring the future — Re-weaving a modern identity

The exhibition’s powerful answer to the crisis it outlines lies in its third and final act, a vibrant showcase of innovation and hope. It argues that for Xiabu to survive, it must confidently step into the future. The first step is inspiration, and the curators find it in a brilliant comparative display of other East Asian ramie traditions. The focus falls on Japan’s Echigo-jofu, a textile from the snowy Niigata region.

An old saying beautifully describes its connection to the climate: it is “spun in snow, woven in snow… snow is the mother of the cloth.” The journey of Echigo-jofu to becoming a national treasure and a UNESCO-recognized intangible cultural heritage provides a powerful blueprint. It demonstrates that with the right combination of cultural storytelling and uncompromising quality, an ancient craft can achieve immense contemporary prestige and value.

This is the climax of the exhibition’s argument: the reimagination of Xiabu is a reality in motion. On display are stunning contemporary applications that lift the fabric from its “folk” context and place it firmly in the 21st century. A tailored blazer showcases Xiabu’s unique texture and structure, offering a breathable, sustainable alternative for modern city wear.

Minimalist tea mats and geometric-patterned curtains leverage its natural, rustic elegance for contemporary interior design. These sophisticated, modern designs move beyond historical reproduction to prove Xiabu’s viability as a high-performance material for a world increasingly drawn to sustainability and authenticity.

Xiabu breathes anew

This must-see exhibition takes visitors on a compelling journey: from revering the deep history and painstaking craft of Xiabu, to understanding the threat of its disappearance, and finally, to feeling inspired by its boundless potential for a new life.

The "breathing fabric" takes its first breath. Raw ramie fibers, the soul of Xiabu, dry in the open air of the Nantou Ancient City.

The success of “Summer’s Breeze” lies in its compelling argument for the craft’s future, distinguishing it from a simple eulogy for a dying art. It powerfully redefines heritage as a living tradition that must adapt, innovate, and breathe to survive. The exhibition does more than display the “breathing fabric” — it animates the craft, giving it a new breath of life, and you, the visitor, leave feeling that fresh, hopeful breeze.