The carving blade as weapon: China's wartime woodcut movement

Writer: Sterling Platt | Editor: Lin Qiuying | From: Original | Updated: 2025-10-29

In the eyes of writer and revolutionary Lu Xun, the woodcut was never merely an art form — it was a weapon. He saw it as a “dagger and a javelin,” a tool capable of carving the unyielding spirit of the Chinese people into stark black and white. This transformation of art into a tool of resistance was the focus of a profound exhibition recently held the Shenzhen Museum titled “Master Engravings: Exhibition of Woodcut Art During the War of Resistance Against Japan.”

The show traced the origins of this powerful medium to 1931, when Lu Xun ignited the New Woodcut Movement (新兴木刻运动) in Shanghai. He championed the woodcut for its revolutionary potential in a time of crisis: it was cheap to produce, easily reproducible for mass distribution, and brutally direct in its message.

He called for a new generation of artists who, in his words, were like “daggers that have just been trampled” — forged in hardship and ready to strike back. Breaking from traditional decorative woodblock printing, these artists embraced a philosophy of “truly facing reality,” laying the ideological and formal groundwork for what would become one of the 20th century's most revolutionary and popular art forms.

These woodcuts are not tranquil, post-war reflections. They are urgent dispatches, carved in the heat of conflict during China's War of Resistance against Japanese Aggression (1937-1945). Created as instruments of national survival, these prints were made during the war, for the war.

This immediacy grants contemporary viewers an unvarnished and deeply authentic perspective, offering a visceral window into the raw emotions and fierce resolve that defined a nation fighting for its existence. They are a testament to an epic of national struggle, etched with what the foreword called“iron strokes and silver hooks,” charting a course from furious protest to the determined work of building a new society.

Forging the weapon

The New Woodcut Movement was born out of a sense of profound crisis. Lu Xun, a literary giant, believed China’s survival depended on a cultural and spiritual awakening, and he sought an artistic weapon fit for this struggle. He championed the woodcut precisely for its utility: its low cost and reproducibility made it ideal for mass communication, while its raw aesthetic could deliver a jolt to the national conscience.

To forge this new tool, Lu Xun urged artists to seize and adapt powerful foreign models, particularly the socially conscious work of European printmakers like Käthe Kollwitz, whose depictions of suffering provided a ready-made language for China's own anguish.

Lu Xun’s most crucial act was ideological. He promoted the "creative print" (创作版画), where the artist personally designs, carves, and prints their work. This was a deliberate break from the traditional separation of elite designersand artisan laborers. By fusing intellectual and manual work, Lu Xun redefined the artist as a hands-on, politically engaged revolutionary — a soldier whose weapon was the carving blade.

He put this theory into practice, organizing a foundational workshop in 1931 to give this new type of artist the technical skills needed to fight on the coming cultural front.

Dispatches from the front

As the war began, the woodcut became a medium for immediate reaction, channeling the shock and fury of the invasion into visual battle cries. Artists in Shanghai and other cities produced raw dispatches from the front, creating a visceral, real-time record of the conflict.

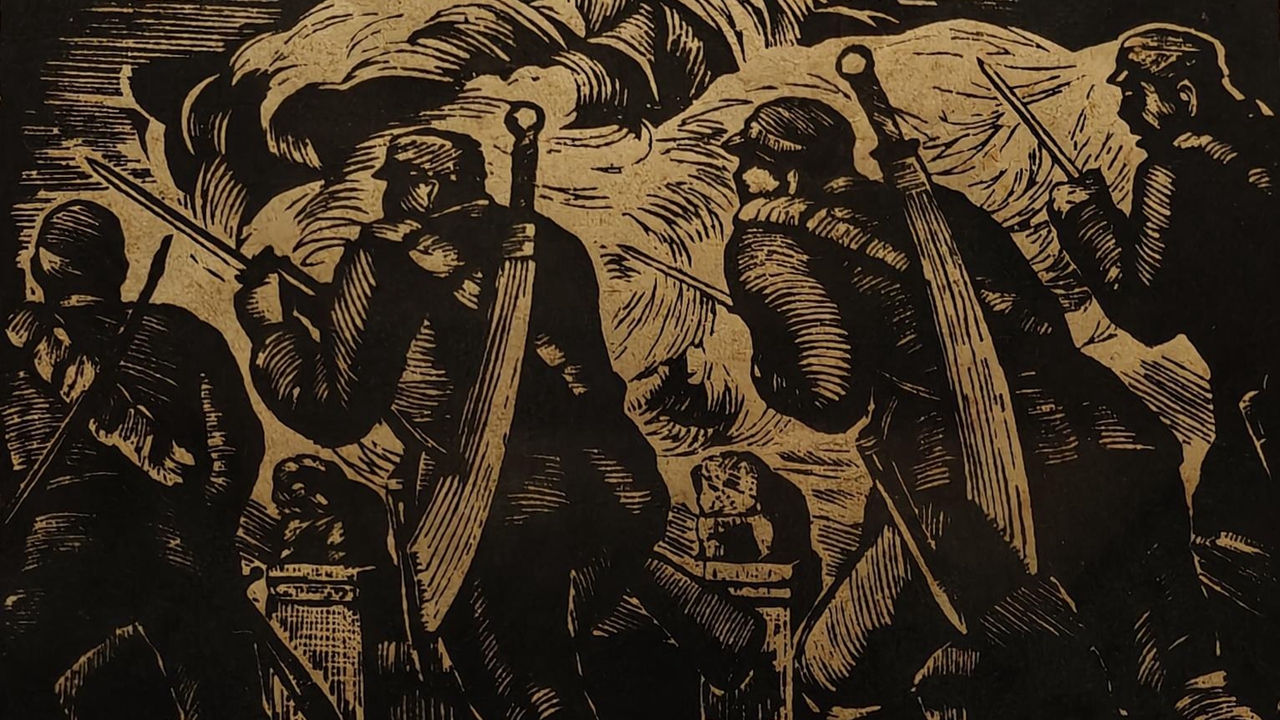

Hu Yichuan’s harrowing print, “The Eight hundred Heroes” (c. 1937-1938), is a prime example of this eyewitness reportage. Commemorating the legendary defense of the Sihang Warehouse, a battle Hu witnessed firsthand, the print plunges the viewer into the brutal chaos of a last stand. There is no polished heroism here — jagged, Expressionist-inspired gouges capture the desperate, claustrophobic reality of the fight, serving as an authentic testament to the tragic cost of courage.

Hu Yichuan’s “The EightHundred Heroes,”an eyewitness account carved with the violent energy of the battle itself.

At the same time, artists created urgent visual propaganda to mobilize the nation. Chen Yanqiao’s “Self-Defense War” (c. 1937-1939) is not a record of a specific battle but an immediate and idealized call to arms. Its clear, heroic figures and strong diagonal lines create a sense of unstoppable momentum, functioning as a direct tool to bolster morale and reflect the defiant spirit of the united front.

Chen Yanqiao’s “Self-Defense War”, a vision of heroic unity, crafted to forge a nation's resolve.

A tool for a new society

As the war evolved into a protracted struggle, the function of the woodcut was recalibrated for a different kind of battle — the long-term fight for survival and the construction of a new society. For artists who moved to the Communist base in Yan'an, the carving blade was retooled from a weapon of protest into a practical instrument of education and state-building, guided by Mao Zedong’s directive that art must serve workers, peasants, and soldiers.

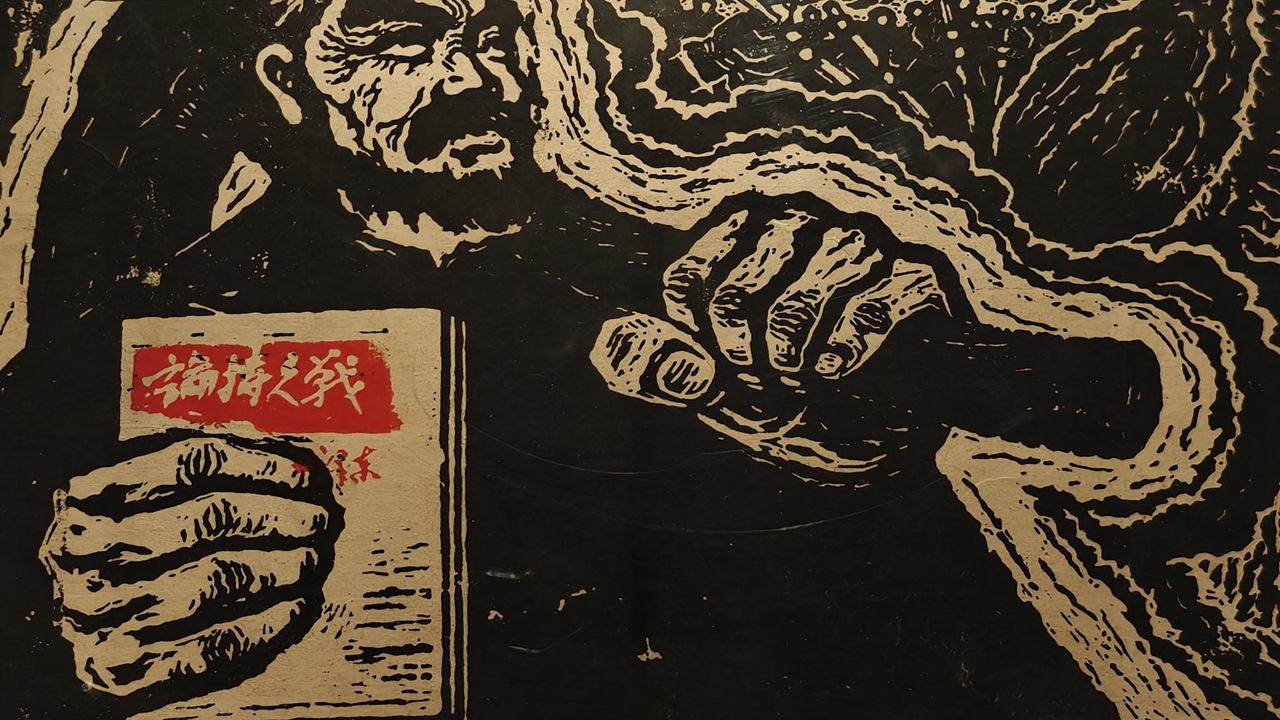

The prints from this period function as practical instruction manuals for a nation at war. The anonymous work “On Protracted War” translates Mao’s military strategy into a visual icon, making complex theory accessible to a peasant fighter.

“On Protracted War” transforms military theory into a powerful icon of popular resistance.

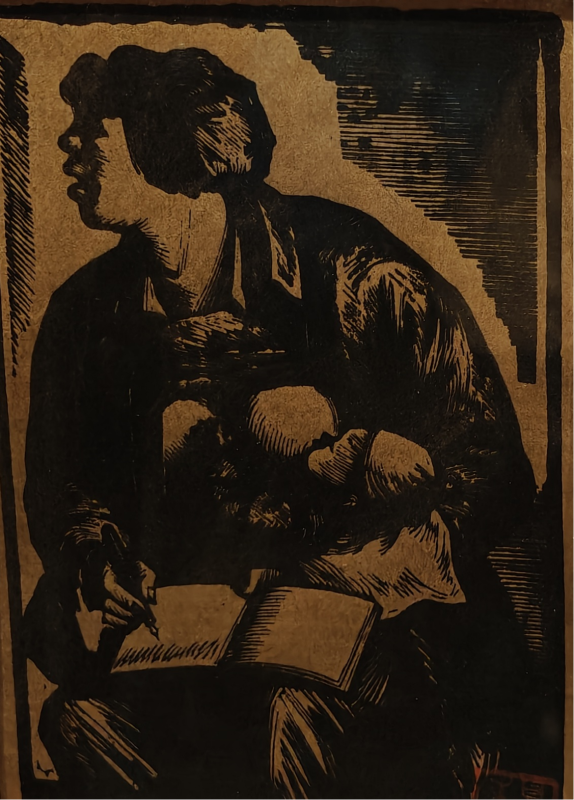

Li Qun’s famous print, “Listening to a Report,” provided a direct model of the new "socialist woman" required for the war effort, one who seamlessly integrates revolutionary duty with family life. It was a visual guide for the new kind of citizen needed to win the war.

Li Qun’s “Listening to a Report”provided a new model for a nation: the revolutionary and the mother as one.

Other prints from Yan'an serve as direct visual aids for wartime policies. Ji Guisen’s “Women's Spinning Group” is a tribute to the Great Production Movement, a critical campaign for economic self-sufficiency.

Ji Guisen’s “Women's Spinning Group” shows the spinning wheel as a weapon in the fight for economic survival.

Wo Zha’s “The Army and the People are One” functions as a field guide to Mao’s doctrine of civilian-military unity, framing the army as a partner to the people.

In Wo Zha’s “The Army and the People are One,”shared labor symbolizes a new bond between soldiers and civilians.

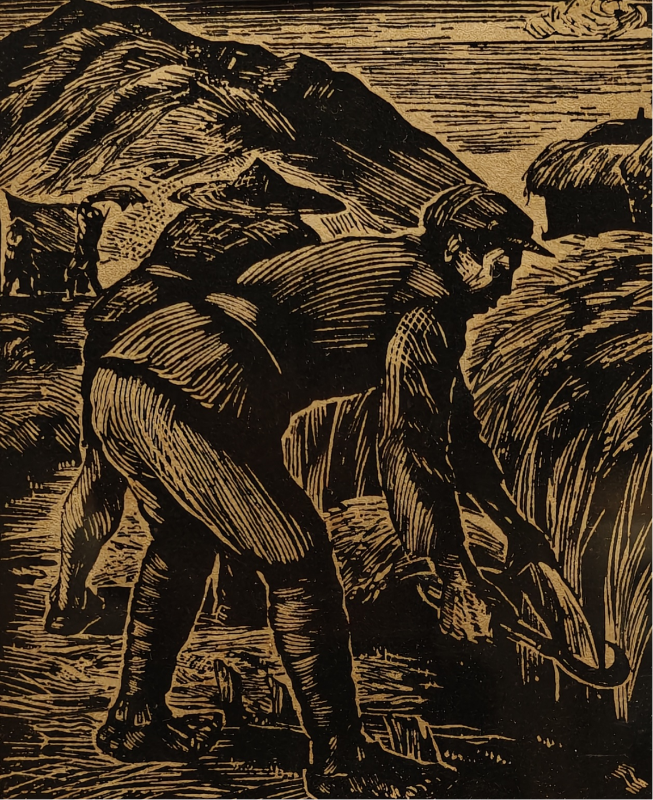

Finally, Zhang Wang's panoramic harvest scene with Mongolian compatriots is a direct visualization of the Party's United Front policy to bring ethnic minorities into the national struggle. Each print is an instrument designed to build a resilient, self-sufficient wartime society.

Zhang Wang'swoodcut shows a shared harvest, serving as a promise of ethnic unity.

The unvarnished reality of victory

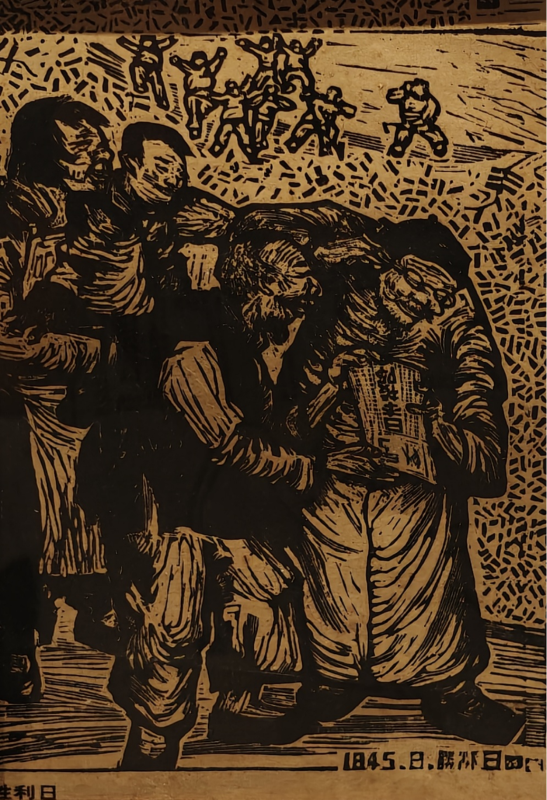

The exhibition culminated with the most authentic dispatch of all: the raw, unfiltered emotion of the end of the war. The anonymous print, “Victory Day” (August 1945), captures the very moment of Japan’s surrender. Eschewing a sanitized narrative of triumphant parades, this print, carved in the immediate aftermath, shows what victory actually felt like for those who survived.

The artist focused on villagers overwhelmed by the news. They embrace and weep, their bodies bent not in celebration but with the sudden release of years of grief and tension. It is a complex storm of joy, relief, and profound sorrow for all that was lost. This print is the "first draft of history," an unvarnished and deeply authentic record of the true cost of survival.

“Victory Day” shows the moment of victory, an outpouring of both profound grief and relief.

Reflections

Together, these prints confirm the power of art when it is used as an instrument of survival. They reveal how the woodcut was forged into a weapon and then continuously adapted to meet the shifting demands of the battlefield — from the jagged blade of protest in the cities to the precision tool of social construction in Yan'an. Though the styles diverged, the function remained the same: to provide an immediate, authentic response to the crisis of war.

These works are far more than historical documents — they are artifacts of the struggle itself, granting us a window into the conflict as it was lived, fought, and felt. They fulfill Lu Xun’s vision of an art that could awaken a people, first by channeling the agony of invasion and later by carving the blueprint for a new society. In these powerful images, we see the story of a war told not in retrospect, but from the front lines, through the enduring power of a simple block of wood.