Ruan master inspired by Chinese classics

Writer: Debra Li | Editor: Vincent Lin | From: Shenzhen Daily | Updated: 2019-09-17

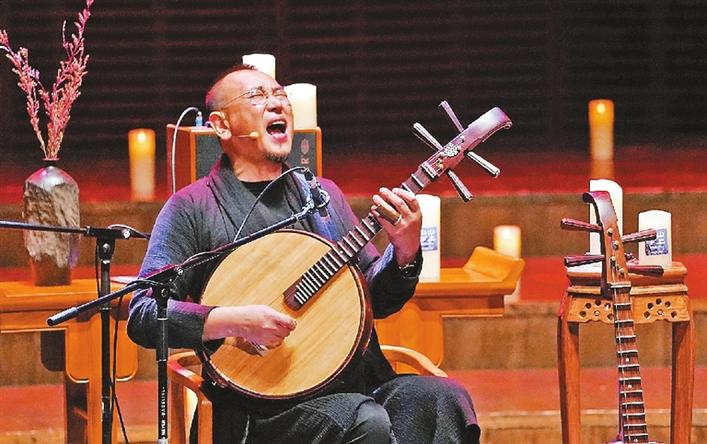

While audiences would no doubt call it an unforgettable evening witnessing a concert by ruan player Feng Mantian and his band at Shenzhen Concert Hall on Thursday, they found it difficult to recall a single melody from the show.

“That is because my music is mostly improvisation,” Feng said during an exclusive interview with Shenzhen Daily before the show.

Along with flutist Ding Xiaokui, keyboardist Zhang Jian and percussionist Zhao Bing, Feng is in the middle of a national tour titled “Up and Down the Mountain: Sacred and Secular,” which kicked off in Xiamen, Fujian Province on April 28 and will last through December.

The first half of the show is “down the mountain,” which is about people’s “joy, anger, sorrow and other feelings commonly experienced in the secular life,” Feng explained. The repertoire included “The Wusuli Boat Song” based on a folk song from Northeast China, “Bringing in the Wine” adapted from a poem by Tang Dynasty (618-907) poet Li Bai and “Xin Tian You Caprice,” which combines popular folk songs from Shaanxi.

“The lyrics are always the same, but the music is largely improvised based on the themes, even for the first-half of the show,” Feng said.

The second half, which has no lyrics, is improvised around five themes. Therefore, audiences get a different show each time they attend one of Feng’s concerts. “The music ‘Up the Mountain’ is very quiet, giving people a time and space for meditation and imagining how our ancestors played and enjoyed music, alone or with friends in a bamboo grove under the moon.” To accompany the music, lights were dimmed to a minimum so that the audience could capture even the slightest sound. “When I stop thinking and feel completely tranquil and at ease with my surroundings, music comes to me naturally,” the 56-year-old legendary musician said.

Ruan player Feng Mantian stages a concert at Shenzhen Concert Hall on Thursday. Han Mo

Feng’s music is a miraculous mix of rock, jazz and Chinese ancient music, formed over the years out of his unique career.

The son of yueqin master Feng Shao-xian, he started to play the violin at 4, and learned yueqin from his father at 6.

At 15, he was recruited into the China National Traditional Orchestra in Beijing and became a ruan player.

“Ruan is not much different from yueqin (also called “moon guitar”), as they both belong to the lute family and have a round, hollow wooden body and four strings. While the yueqin has a short fretted neck, the ruan has a long one,” Feng explained. The two instruments were both invented around the time of the Jin Dynasty (265-420).

Legend has it that Ruan Xian of the Jin Dynasty was adept at the instrument, and one such instrument was excavated from his tomb in the Tang Dynasty (618-907), therefore giving his name to it.

A man of restless energy, Feng embraced every type of music he could find in his teenage years. He spent hours and hours listening to music cassettes, from classical Western symphonies to rock bands like The Beatles and jazz fusion.

For a time, he was so fascinated with playing guitar that he formed rock band “White Angel” with friends. Back in the 1990s, he had traveled to Shenzhen and performed in the city’s night clubs.

Though never losing his passion for ruan-playing and Chinese music, Feng at one time felt frustrated by his chosen path.

“Chinese traditions were thought of as inferior to classical Western music, and even the best work of our composers took the form of Western music,” Feng said.

“Take the example of Huang Haihuai’s ‘Horse Racing,’ which is in fact a three-part sonata written for erhu.”

While the unique sounds of Mongolian, African and Turkish musicians have all found inspiration from their cultural traditions, Feng said many Chinese have become followers of Western music.

“It’s not to deny that Western music is profound and beautiful,” Feng said. “But there are also gems from Chinese traditions that we can rediscover and thereby find our confidence and feel proud.”

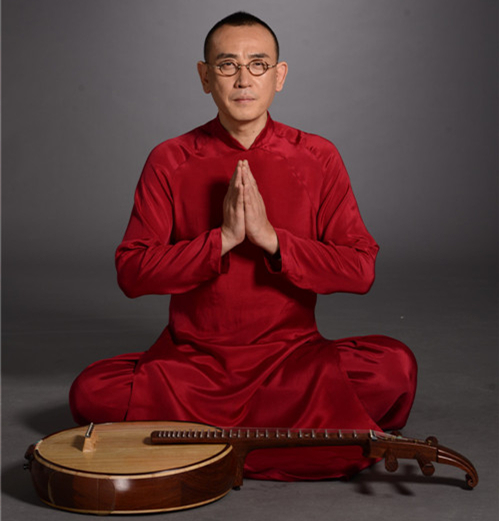

The ruan, also known as the Han pipa, traditionally had no hole on the front of its round wooden body, Feng explained. But people added a hole to make it look more like guitar and give it a louder sound in the 1950s, which is, in Feng’s opinion, evidence of being overwhelmed by Western traditions. To make it right, Feng spent years reinventing the instrument, moving the hole in the upper side of its body and making it more close to the ancient instrument.

“The ruan’s round wooden body symbolizes the ground, the long neck stands for the sky, the four strings respond to four seasons of the year, and the 24 frets relate to 24 solar terms,” Feng said. The hole he leaves on the upper side is close to the player’s heart when they hold it, because “music is meant to tell true feelings and genuine thoughts,” according to the “Book of Rites” (礼记).

Although thinking his ideal life would be a quiet one filled with music for himself and friends, Feng and his band are constantly on tours. His next stop will be a jazz festival in Shanghai.

His two albums, featuring the repertoire from the tour, will be released by Deutsche Grammophon, although Feng is kind of lukewarm about albums.

“Recordings are just memories. They cannot compare with live performances,” Feng said.